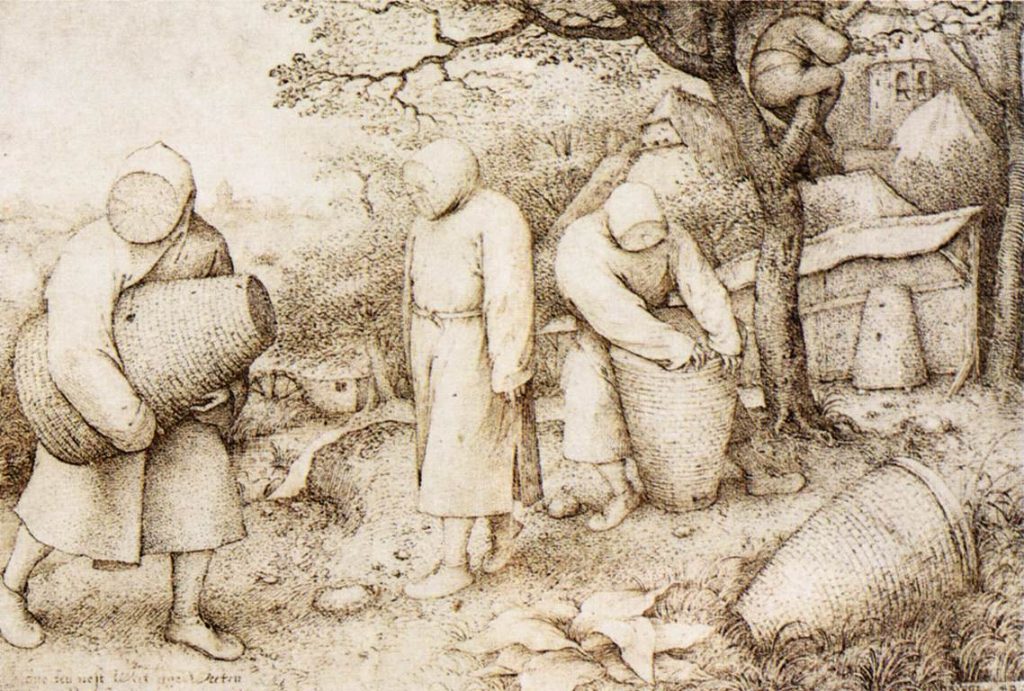

This blog post is an adaptation of a History Happy Hour talk given last year during the 2019 season, “Bees, their Friends, and their Uses” by Tim Betz, Morgan Log House Executive Director. Keep an eye out for more History Happy Hours (both online and in person) in the coming weeks!

Bees and humans have enjoyed a long relationship.

The earliest archaeological evidence of an interaction between humans and bees is honey hunting in early prehistory: which has been seen in cave paintings in Spain from around 8,000 years ago. Honey hunting is a type of foraging where honey is collected from wild hives rather than keeping bees in domesticated hives.

The practice of keeping bees is ancient. Archaeologically, we know that the ancient Egyptians were keepers of bees, as the Egyptians used honey to sweeten foods, preserve foods, as a medical salve, and as a tool for mummification. The Egyptians kept hives on small boats which they would move up and down the lush banks of the Nile in search of flowers to pollinate. Beekeeping is mentioned at length by ancient writers like Virgil, Pliny the Elder, and Aristotle, Greek and Roman naturalists and historians. Outside of Europe, beekeeping was also occurring in China since antiquity. Likewise, the Maya domesticated a sort of sting-less bee long before European contact. By the time of Europe’s encounter with America, the raising of bees was happening throughout the “Old World” and was an important part of the ecosystem.

When European colonists came to America, they brought their bees with them, starting in 1622. There were, of course, native bees throughout the Americas, such as bumblebees and stingless bees, but they were not the Europeanized bees that were (and still are) used in beekeeping. European bees are better honey producers, and were seen as more useful for colonial planters. After 1622, the cultivation of bees became an important part of life in the American colonies. In the eighteenth century, Thomas Jefferson wrote about bee cultivation, saying “the honey-bee is not a native of our continent…The Indians concur with us in the tradition that it was brought from Europe; but, when, and by whom, we know not. The bees have generally extended themselves into the country, a little in advance of the white settlers. The Indians therefore call them the white man’s fly, and consider their approach as indicating the approach of the settlements of the whites.”

An interesting side story of beekeeping and the body is the thought that beekeepers needed to be morally and physically pure in order to visit their bees, who would punish the impure beekeeper for their transgressions. A Roman writer noted that “very great care must be taken by the man in charge, when he must handle the hives, that the day before he has abstained from sexual relations, and does not approach them when drunk, and only after washing himself, and that he abstain from all edibles which have a strong flavor.”

A later writer, Thomas Hill, wrote that “The keeper of bees, who mindeth to handle and look into hives, ought the day before to refraine from the veneriall Act, not a person fearefull, nor comming to the hive with unwashed hands and face, adn one that ought to refrain in a manner from all smelling meats, poudered meats, fried meates, and all other meates that doe stincke, like as the Leekes, the Onions, and the Garlick, and such like, which the Bees greatlie abhoree, besides to be then sweet of body, cleanie in apparrell, minding to come unto their hives, for in all cleanlinesse and sweetnes the bees are much delighted.”

While bees do not take this sort of discretion in stinging people (they only sting when it’s the last possible resort), this shows that bees and their keeping had gotten tied into cultural and moral ideas in Europe and in the colonial period.

Many used bees as a metaphor for industrious work. Bee society was considered perfectly ordered and industrious. Bees were also seen as honoring their monarch and performing their task well for the hive, which is something that the Crown wished to enforce among its colonists. The symbol of the beehive for a good society was co-opted by the Continental Congress in 1779, when they used the symbol of a bee skep and thirteen stars on currency as a symbol of the industrious new nation.

Many colonial farmers (and households) would have kept bees as an important livestock. Bees had a variety of uses. Most importantly, honey from bees was used as a sweetener. In the colonial period, sugar was a luxury good and was imported to the colonies from sugar producing islands like Jamaica, where it was produced through horrific slave labor. Honey provided a cheaper, local, sweetening alternative. Likewise, bees provided another important resource: wax.

Beeswax was an important ingredient for the colonial home. It could be used as a lubricant and as a waterproofer. More importantly, it could also be used to make candles. In the eighteenth century, candles and lamps would be the only source of light in the home at night. Beeswax proved to be a reliable material for candles, which burned for a lengthy period of time and did not stink like some alternatives (such as tallow, or rendered animal fat). Wax would be melted and used to make candles in the fall. Often, a home would make enough candles to get through the entire year. While now we might think of the colonial home as lit by beautiful candlelight, the reality is that candles were an important resource to be rationed. Very often, in a home like the Morgan Log House, people probably only used one candle at night. This was a time before our modern reality of light pollution and electricity: the darkness of the eighteenth century night would be hard for us to imagine.

While bees were an import to the American continent, beeswax proved to be a valuable American export. In 1771, twenty-nine thousand two hundred and sixty one pounds of beeswax were exported from the port of Philadelphia

Paging Dr. Bee: Bees and their Colonial Medical Uses

With this long history between people and bees, it is only natural, then, that we would move to using bees and their byproducts for medical use.

Honey was long part of medicine. In part, this could be because honey is a natural preservative: it rarely goes rancid and contains some naturally occurring hydrogen peroxide, so it is antiseptic. Honey was, historically, used as a method of preservation, for the travel and keeping of all sorts of thing. We know, too, that honey was used for the preservation of bodies, including by ancient Egyptians in some mummification and the body of Alexander the Great.

Here are some uses for bees medicinally in the eighteenth century, taken from medical receipt books from Pennsylvania.

For a burn:

“Take ye fat of ye Guts of a Goose beet it with a wooden perstle, melt it over ye fire & skim it let it stand to setle, pour it into a Galy pot it will keep all ye year apoint either Burn or Scald with it well, it will take out ye fire & give ease, dress it with ys 5 dayes together twice a day. Then take as much bees wax & salet oyle as well make it a plyable salve, not too stiff, yn spread it upon fine cloth & lay it on to heal if it is deep take a little lint dip it in ye sale melted”

In a way, this makes some sense, as honey is an antiseptic and is antimicrobial.

Other uses are more dubious. Ranging from curing baldness ( “Rub that Part Morning and Evening, with Onions, ’till it is red; and rub it afterwards with Honey,” or “When you take ye bees take ym & Hony & Rosemary & still it wet your Hair with it every morn & evening with a spunge or ye Leaves of ye hemeboyle ym in water & wash yr head”) and healing a venomous bite “Apply a little Venice Treacle and a Poultis of bruised Plantane and Honey:” While neither of these cures will work for their intended purposes, persay, they might make the person feel better, especially with the use of Venice Treacle on a venomous bite. Venice Treacle was a medical concoction that contained 64 ingredients, including viper flesh, cinnamon, asphalt, and gum arabic. The active ingredient was opium. Opium was introduced to Europe during the crusades, and was used medically and recreationally. Then, as now, it was highly addictive.

Additionally, honey could also be used to cure rheumatism, such as when one medical receipt book said that someone should “mix Flour and Brimstone with Honey, equal Quantyties. Take three Tea spoonfuls at Night, two in the Morning; and one afterwards Morning and Evening, till cured. This succeeds oftener than any Remedy I have found.”

Honey and Scrofula, the King’s Evil

Many recipes are for the curing of the King’s Evil, also known as scrofula. The King’s Evil is a glandular swelling, that was probably a form of tuberculosis. It was called that because the French and English believed that their monarch (the French King or the English King, but not both) could cure it by touching those who were afflicted. In the absence of the king’s touch, coins that were touched by the king would work. In the absence of a king or coins touched by him, there were other remedies, such as: “ set a Quarter of Honey by the Fire to melt. When it is cold, strew into it a Pound and a half of Quick-Lime beat very fine, and searsed through a Hair Sieve. Stir this about till it boil up of itself into a hard Lump. Beat this when cold very fine, and searse it, as before. Take of this as much as lies on a Shilling in a Glass of Water every Morning fasting; an Hour before Breakfast, at four in the Afternoon, and at going to Bed:”

This is just a sampling of the ways that honey was used medicinally in the colonial period. It’s important to remember that, while modern medicine has come a far way from the sorts of treatments talked about here, when they were written doctors, physicians, and other medical practitioners felt that these were the best of modern medicine. People sought these treatments because of a genuine belief in their ability to work: and sometimes belief is just enough.

Bees and their byproducts are still used medicinally in the modern era. Honey has many functions. It’s a great additive for tea and is known to help a sore thought. Some research points towards the use of bee venom being helpful for treating and preventing rheumatoid arthritis.

Bees are an important part of our ecosystem, and we rely on them to pollinate food sources. Today, they are threatened by pollution and pests such as mites.

For more on colonial medicine, visit our online version of 2019 exhibit Leeches, Purging, and Magic: the Care and Healing of the Colonial Body by clicking here.

The Morgan Log House received a grant for educational bee hives on our property from the Whole Kids Foundation and the Bee Cause Project in 2019. When we reopen for tours, stop by and see our hives. We even have Morgan Log House honey for sale!