This is the story of Daniel Boone’s maternal grandparents, Edward and Elizabeth Morgan, and the world of which they were a part.

Early eighteenth century records, particularly records for those who were not particularly wealthy, are notoriously difficult things from which to draw a life. We do know a couple things about Edward and Elizabeth. Firstly they were immigrants—though when exactly they immigrated to the New World we are not sure. Secondly, we know they emigrated from Wales though, again, we are foggy on the “when.” Third, we know that they were Quakers, members of the Society of Friends and worshiped at meeting in Gwenydd, PA. We also know that they purchased a tract of land in 1708—300 or so odd acres in Towamencin–which has been whittled down to the acre and a half that the Morgan Log House now stands on. We know that in 1708 they bought a small house—a small fraction of what is now standing at the site today, and we know that they lived there with their eleven children, one of whom, Sarah Morgan, would marry Squire Boone and give birth to Daniel in 1734. We know that Edward was a cloth maker, a tailor, and a farmer, using his land to make a way for himself in the New World as many immigrants had and continue to do to this day.

Other than this, we know very little.

It is the job of historians to piece together the fragments of their lives from what we can deduce about them from the documentation that survives. That is what I hope this talk will do. This will not be the life story of Edward and Elizabeth. That is almost impossible to do with the documentary record that we have. But it is my hope to go around Edward and Elizabeth–and live in their world for a bit–in order to put together their lives and make some educated assumptions about them. Together, let us piece together their lives from those scant details we know about them—that they were Welsh immigrants, they were Quakers, and they purchased a plot of land in Towamencin, in the colony of Pennsylvania, in 1708.

Let’s try to bring Edward and Elizabeth back to life.

The Quakers

We do know that Edward and Elizabeth were Quakers, which might have been one of the reasons they emigrated to America.

The Quakers, officially known as the Religious Society of Friends, began in the seventeenth century in England.

The movement was founded by George Fox, who began the movement in 1647 by preaching publicly. Eventually, the Society of Friends formed around him. Fox was preaching at a time of great religious dissent as Christian denominations had begun to spring up around England with great zeal. In today’s world, we take for granted the number of Christian denominations–to us there are many churches that cater to the religious needs of many people. For those living in the eighteenth century, these were complicated, confusing, and disputed times. Small dissents in small theological matters could be a matter of life or death. This time of religious confusion granted Fox a platform upon which to preach and attracted followers to his simple teachings. Fox did not wish to start his own sect. Rather, he sought to return Christianity to its original simplicity through a combination of strict reliance on the scriptures and personal experience. Eventually, his preaching evolved into the organized Society of Friends. Though Fox and his followers were persecuted and marginalized, by the end of the 1650s the Society became increasingly organized and legislated.

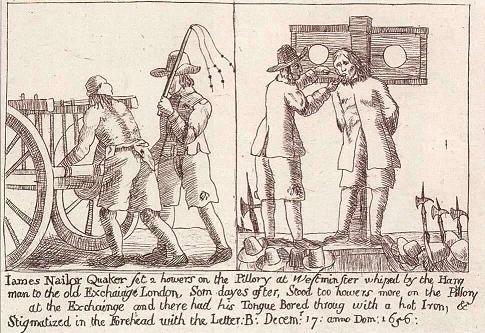

Members of the Religious Society of Friends suffered much persecution in England–they were dissenters of the Church of England and pacifists. They would not take part in the Crown’s wars nor would they pay their taxes, as they believed (rightly) that taxes would go to support military ventures. They believed in total equality and would not bow down to the aristocracy. They would not take oaths, meaning that they could not take an oath of allegiance to the king. Quakers, as a result of all of these, were viewed with great suspicion and suffered violence and marginalization.

Quakers suffered this treatment throughout the British Empire. Edward Burrough, in his 1660 A Declaration of the Sad and Great Persecution and Martyrdom of the People of God, Called Quakers, in New England for the Worshipping of God details the mistreatment and murder of those who practiced the faith. Burrough notes that, in New England, “22 [Quakers] have been banished upon pain of death, 3 have been martyred, 3 have had their right ears cut, 01 hath been burned in the hand with the letter H, 31 persons have received 650 stripes, 1 was beat while his Body was like a jelly, several were beat with pitched ropes, one thousand forty five pounds worth of goods hath been taken from them (being poor men) for meeting together in the fear of the Lord, and for keeping the Commands of Christ, and one now lyeth in iron fetters, condemned to die.” This sort of treatment had been encountered by the members of the Religious Society of Friends throughout the world–there simply was no place for them in a seventeenth century world and they endured great pain as a result.

Enter William Penn.

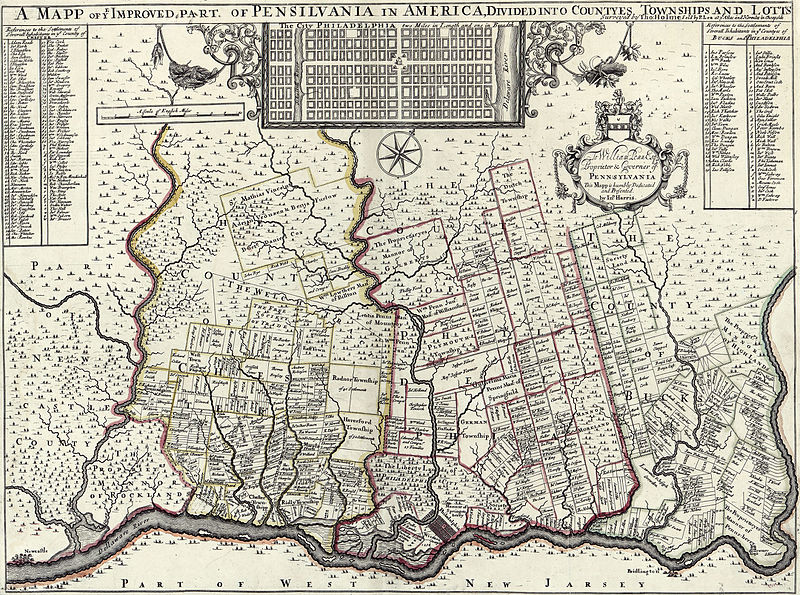

In 1680, William Penn petitioned the Crown for land in which the Quakers could settle. The King Charles signed a charter in March 1681, making William Penn the proprietor of land west of Jersey, which he originally called Sylvania, which is Latin for woods. Charles later changed the name to Pennsylvania (Penn’s woods) to honor William Penn’s father, Admiral Sir William Penn, for services and debts rendered the Crown–debts paid by the land grant of Penn’s woods..

Penn had a particularly unique brand of idealism, which made Pennsylvania distinct among the original thirteen colonies. Penn sought to found his colony on his newfound Quaker ideals–religious tolerance, diversity, and representative government. Penn believed that his colony would be a “Holy Experiment.” It was his view that a foundation in Quaker teaching would lead to stronger governments and wealthier societies. He noted that “Religion and Policy are two distinct things, have two different ends, and may be fully prosecuted without respect on to the other.” This would, of course, grow to become one of our national ideals–the separation of Church and State, and ideas of religious liberty and worship according to one’s conscience.

Though founded as a Quaker stronghold, Pennsylvania quickly became a very diverse colony. It was the only colony of the original thirteen to not have an official established Church. Instead, the principle of religious tolerance was the guiding law. Penn invited other groups into Pennsylvania who were suffering persecution, and it quickly became a colonial safe harbor of religious expression. Religious tolerance had its limits, though. Only Christians could vote or hold public office.

Penn advocated the fair treatment of indigenous inhabitants, so, at least in the early period of the colony, the Lenape lived unmolested near the Delaware River. Other settlers, such as the Dutch and Swedes, had been trading and farming in the region before Penn and were allowed to continue after. More Europeans arrived on Penn’s invitation in the 1680s, bringing with them African and Caribbean slaves. Inhabitants ranged from the very wealthy to the very poor, from free laborers to indentured servants and the enslaved, and from a variety of ethnic, economic, and racial backgrounds. As Penn himself noted, after a Lenape treaty, “We meet on the broad pathway of good faith and good-will; no advantage shall be taken on either side, but all shall be openness and love. We are the same as if one man’s body was to be divided into two parts; we are of one flesh and one blood.” Of course, viewing early Penn’s woods as a place of great tolerance and love and peace is grossly oversimplifying the lived experience of settlers. There was still gross inequality, enslavement (Quakers would only forbid and actively oppose slavery in the next century), and periods of hardship, difficulty, and violence–we should not view Penn’s woods as an ideal, peaceful kingdom on earth.

The first wave of Quakers arrived with Penn on October 27, 1682 aboard the ship Welcome to establish the Holy Experiment. As Samuel McPherson Janney noted in his 1861 book History of the Religious Society of Friends from its Rise to the Year 1828, “The Friends, soon after their arrival, were careful to establish, in every neighborhood, meetings for divine worship, where they offered up with grateful thanks to the Father of Spirits for the many blessings they enjoyed.” The Quakers likewise found good land and water in Penn’s woods. A 1683 letter noted that “And for our condition as men, blessed be God! We are satisfied; the countries are good- the land, the water, and the air-room enough for many thousands to live plentifully, and the black-lands much the best; good increase of labor, all sorts of grain, provision sufficient, and by reason of many giving themselves to husbandry, there is likely to be great fruitfulness in sometime. But they that come upon a mere outward account must work, or be able to maintain such as can. Fowl, fish, and venison are plentiful; and of pork and beef no want, considering that about two thousand people came into this river last year. Dear friends and brethren, we have no cause to murmur, our lot is fallen every way in a goodly place, and the love of God is, and growing, among us, and w are a family at peace within ourselves, and truly great is our joy therefore.” Long and joyful sentiments, to be sure–but such words falling upon ears in the Old World quickly sprung into action, and many began to pour into the region by the turn of the century.

We can piece together something of the religious affiliation of Edward and Elizabeth, knowing that they were married at the Quaker meeting house in Gwenydd, which still stands today. Through documentation, we know that Edward and Elizabeth took part in the community of the church, having been listed as witnesses for the marriages of friends as well as taking part in various tasks. Edward and Elizabeth Morgan, along with their children John, William, and Morgan, sign the marriage certificate of their daughter, Elizabeth Morgan, to Cadwallader Morris on March 24, 1710. Likewise, we do know that Squire Boone and Sarah Morgan declared their intention to marry on the 20th of May, 1720 at the Gwenydd meeting house.

Of course, it is hard to infer from this the depth of their religious beliefs. Personal religious belief is just that–personal. While Edward and Elizabeth attended meeting and were a part of their faith community, we do not know the extent of the belief in their hearts. However, from their involvement in Gwenydd, we can surmise that they were part of a religious community with like minded, fellow Welshmen, who lived in the Welsh tract and followed their Quaker beliefs.

The Welsh Tract and the Welsh Quakers

Why did those Welsh people come here? Why did Edward and Elizabeth choose to buy land in Towamencin? There was, after all, a whole big continent to expand onto. Why did Edward and Elizabeth choose where they did?

We can assume that there were several reasons: available land and proximity to the city of Philadelphia among them. I think, though, a good candidate for why is the idea of the Welsh Tract.

Welsh Quakers particularly wished to find a place of autonomy, and so, in 1684 a group of Welsh Quaker petitioners lead by John Roberts petitioned William Penn for a tract of land that would be a separate country, with all official business being conducted in the Welsh language. The tract was granted in March of that year—with an agreed upon 40,000 acres north of Philadelphia being set aside for a Welsh tract and barony. The boundaries of the tract—now part of Montgomery, Chester, and Delaware counties—were established in 1687, however by the end of the century that area would begin to be portioned off, meaning that while there was a heavy amount of Welsh Quakers in the area it never became fully autonomous as its petitioners had hoped for.

Edward and Elizabeth clearly chose to live in the Welsh tract to be among their fellow Welshmen, who sought, at least early on, to maintain their Welshness in America through maintaining their language, customs, and way of law. This desire to maintain Welshness was as unsuccessful as trying to set up an autonomous Welsh county. To fully understand, we must look at Welsh culture, tradition, language, and experience.

Interesting, even from its earliest periods, the spoken and written language of the Welsh tract was not linguistically pure to the Welsh language, despite the best hopes of the petitioners. Many of the settlers there spoke English fluently. News of the first arrival of Welsh immigrants was sent back to Wales in a letter written–in English. Quaker services held in the Welsh tract were done in both English and Welsh, as many members of the congregation could not decipher Welsh. However, the ability to maintain some Welsh language was aided by the fact that anyone–Welsh speakers among them–could speak from their inner light at a Quaker service, as there was no ordained order of Quaker ministers–only the congregation. This allowed for the continuation of the language in a religious context. Eventually, like the Welsh Tract, a Welsh identity began to melt away, as people referred to themselves as “Quaker Pennsylvanians” instead of “Welshmen.” For one, this could have been a decision made based on a desire for upward mobility. Embracing the English language and allowing for cultural fluidity allowed Welsh immigrants in the Welsh Tract to interact with their non-Welsh neighbors, conduct business affair, and seize opportunities that might not have been allowed to them without a grasp of the English language and customs. At the time of the American Revolution, most if not all of the Welshmen in the Welsh Tract had assimilated into the colonial society. There remained small clusters of independent Welsh speakers, but, by and large, the local culture had mixed.

It seems, too, that this blending was not forced by English speakers nor was there strong antagonism between the English and the Welsh. Many Welsh settlers spoke English before their arrival or learned it soon after, as it had become a colonial lingua franca that was adopted with some vigor, replacing the desires of an autonomous Welsh speaking area in less than a decade. An anguished Welsh Baptist minister in the area wrote home in 1712, noting that “the English is swallowing up [the Welsh language].” Indeed, even in the beginning eighteenth century, the American melting pot was at a full boil, with the King’s English becoming an administrative necessity.

It’s impossible for us to know what the linguistic abilities of Edward and Elizabeth were–most certainly we can deduce that they spoke Welsh and English with some ability. By the time of their arrival in Towamencin in what was once the Welsh Tract in 1708, it would seem that many of their neighbors, though Welsh and Quaker, would have been speaking English (and some Welsh). Language is one of those notoriously difficult things to pinpoint. Simply–we cannot converse with those who lived in the past. What we do have is written documents. The will and probate record of one of Edward and Elizabeth’s children, Morgan Morgan, which was written in 1727, is written in perfect, eighteenth century English. It is key to note, though that any written document is not a barometer for the spoken language. While Morgan Morgan’s will is in English, English was also the administrative language. Will’s and probates follow a strict formula of words and expressions, which follow little to no variation from one will to another written in a particular place at a particular time–simply, they are written in what we could call eighteenth century legal-esse. Additionally, the will was not written by Morgan Morgan–only signed by him–as would most legal documents.

But what of other written texts? For the Morgans, we have none. Even if we did, they would not be a great indicator of their Welsh or English ability. If you could write, generally written language is a couple years to decades behind spoken language–meaning changes and nuances in ideas and cultural assimilation are notoriously difficult to piece together from written texts anyway! Simply, short of a time machine, we will never know how Edward and Elizabeth spoke at home or with their neighbores.

Like language, it is also difficult to piece together lived cultural experience. Welsh settlers like the Morgans certainly brought more Welshness with them to the New World than their language. This would include Welsh foods, customs, folklore, ways of living, conceptualizations, and ideologies. Certainly, we can pinpoint Welsh foods–things like Welsh Cakes and Welsh Rarebit–Welsh customs and celebrations, like the summer Calan Haf, but we have no idea as to what level of involvement the Morgans had with these. Elizabeth Morgan might have made Welsh Rarebit all the time-or she might not have. These familial and individualized nuances are lost to us as the Morgans as living people are lost to us.

Quite simply–we got nothing.

Admittedly, this is a bit pessimistic: but it is, at its heart, responsible and realistic. We have no proof about how much English our Morgans spoke if they spoke it at all, and for that same measure we have no proof nor can we begin to surmise the amount of Welsh cultural traditions that the Morgans held onto in the New World. It’s not historically wise to guess what their spoken language was, what their lived cultural experience was: anything. I think, though, it is not radical to assume that, like the rest of their neighbors, they sought to hold onto some of their traditions (of which language is just one part) while at the same time blend into their new surroundings as “Quaker Pennsylvanians.” We do have a clue though–in a Morgan family bible printed in 1837 by the British Foreign Bible Society in Welsh and currently in the Morgan Log House’s collection. This doesn’t say much about Edward and Elizabeth, persay, but it does say that their descendants–their great grandchildren–had some desire to maintain their Welshness–enough to acquire a Bible in their mother-tongue. It is a tale, then, of living and changing and growing–and holding onto some traditions and forming new ones.

As an immigrant nation, this is a story we have had from our beginnings and a story that we continue to have.

The Colonial Experience

What can we piece together about the lives of the Morgan’s from this collective information?

What was the lived colonial experience for the Morgans and their neighbors living in Penn’s Holy Experiment in the somewhat failed Welsh Tract?

First off, what does it mean to be colonial? It’s far more than just a word meaning “oldie timey.” Edward and Elizabeth certainly were living in a colonial world, as colonial subjects of the British king—a trend that would continue until their descendants (and in fact the descendants of immigrants just like them) decided in 1776 that they held these truths to be self-evident, that all men are entitled to certain liberties, and, among them, are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Those self-evident truths—or in fact, the idea of an autonomous American nation—were not a part of the colonial Pennsylvanian’s worldview in 1708—it was a long century of continued frayed relations between the colonies and the mother country to arrive at that point. While Penn’s petitioner’s asked him for an autonomous Welsh barony, it never became autonomous. It remained, as it always had, part of Penn’s woods which were, squarely, part of the British Empire.

To think about the worldview of Edward and Elizabeth we have to think about the journey that they took from Wales to the New World. Erase first from your mind all thoughts of what modern travel is. Unfortunately, we don’t know for sure when the Morgans emigrated, what boat they were on, and what the circumstances of that voyage were. However, we do have the account of Edward Foulke, who emigrated to the New World from Wales, becoming one of the original settlers of Gwynedd township in 1698. Foulke’s party set sail on April 17, 1698 on the ship Robert and Elizabeth, stopping in Ireland before sailing for Pennsylvania in May, spending eleven weeks at sea before arriving at port in Philadelphia. The voyage was less than ideal. As Foulke notes, “The sore distemper of the bloody flux broke out in the vessel, of which died five and forty persons in our passage; the distemper was so mortal that two or three corpses were cast overboard everyday while it lasted. But through the favor and mercy of Divine Providence, I, with my wife and nine children, escaped that sore mortality, and arrived safe in Philadelphia.” Bloody flux is what we today would call dysentery, an intestinal infection that leads to bloody diarrhea. Today, dysentery can be cured with a combination of antibiotics and oral rehydration. It is horrible, but livable, with recovery happening within ten days and total recovery after four weeks. Dysentery is still a problem–with people dying of it in developing countries throughout the world. Like in developing countries, in the seventeenth century, it was a serious medical problem that could easily lead to death through dehydration and other infections throughout the body.

To fully grasp what Edward and Elizabeth were doing, we have to peel back any notions of travel that we have today. We live in an explored world. For many of us, travel across the Atlantic would be a big deal–planning and money would be involved, as would purchasing airline tickets, getting to the airport, going through security. It is, however, doable. The journey that took Foulke eleven weeks would take us less than eleven hours. We could check the weather of where we’re going before we get there. We can look at the things that we’ll encounter. We can consult maps, looking at places to see, places to eat, places to sleep. Out Welsh settlers would have had none of those luxuries. They were getting on a ship and going somewhere they had never been. And travel was a dangerous risk. Now we get on a plane and we know that, almost with certainty, we’ll get where we need to go. Ocean travel in the seventeenth century was far from a guarantee-it was an adventure that could end with death by the bloody flux, sinking in a storm, or starvation on a raft. It was dangerous and uncertain. Our Welsh immigrants were going to somewhere they had never been with only the things they could carry and nothing else. They could not go home to check on their friends. They could not call and certainly they could not email. They could send a letter–but it would take eleven weeks to get home and then eleven more weeks for a reply. Far from an actual conversation. Think of transatlantic travel in the seventeenth century as something more akin to traveling to Mars than flying across the Atlantic. It was far, dangerous, and unexplored.

At the present, we do not have any documentation about what sorts of things the Morgans themselves owned.

We do know a bit about the land that they acquired. They purchased 300 acres of land from Griffith Jones in 1708, and on that was a dwelling house that became their one. In September 1714, Morgan acquired another 500 acres from George Claypoole, meaning that by 1714 he had a decent sized farm parcel of 800 acres. For comparison, Edward Foulke purchased 700 acres of land upon his arrival. Likewise, other locals had comparably sized plots. Thomas Evan had 1049 acres, Robert John had 720, Cadwallader Evan had 609, John Hugh had 648. While 800 acres seems like a lot for us, for those settling the Welsh tract is was a fairly decent sized plot of land.

We know a bit about the place where they lived.

Currently, what we call the Morgan Log House is a large, four story, log structure. We have to peel back from the current reality of the house, which was lived in until 1963, when it was saved and restored to be the historic house that it is today.

The building itself raised many questions for those restoring it. For starters, it was an odd sort of structure that was really two separate buildings placed together, a smaller part on the western part of the building and a larger part to the east. The western structure was in a very poor state of preservation and was torn down, as those working on the building believed that it was added onto the larger structure since it was smaller.

Restoration of the building and research into the history commenced in 1970. At that time there were two ways to date a structure. One was by architectural features such as wood and nails. The other was through deed research, as very often buildings are described in deeds.

The restoration workers thought that the building appeared to have been built in the mid-1700s based on the material evidence that they were encountering. However, deed research finds a sale of 309 acres with a dwelling to Edward Morgan for 72 pounds 16 shillings. This means that either the structure was heavily altered since Edward Morgan purchased it in 1708 or was a different building entirely. As a result, early on there was a conflict in accurately dating the building. Work continued and the site was opened in 1976, but the questions remained.

Today, there is more technology available to accurately date paint, plaster, and wood. However, the one that we can gain the most information from is dendrochronology, which uses tree rings to assess the age of wood. The width of tree rings, which grow every year, is affected by atmospheric phenomenon and weather. Through comparing the widths of tree rings in various wood samples, it is possible to create a timeline that allows for the accurate aging of wood. About 12 years ago a dendrochronological study was done on the Log House and it was determined that the wood used in the log structure was from about 1770. This agrees with the material evidence that the restoration workers found.

Since the smaller structure on the western side of the building could not be dated accurately due to alterations and its poor condition it was decided to tear it down and focus on the east-side log building, which dendrochronology showed was dated from the 1770s. Further research on the extant floor joists on the western side show that the smaller structure dated from the early 1700s, and was probably the building that the Morgans purchased in 1708. As a result, the original Morgan Log House–that Edward and Elizabeth lived in– no longer exists. The earlier structure was demolished.

While we don’t have the original Log House from 1708, we can accurately present the history of the property. A small one room building was purchased by Edward Morgan in 1708, which was demolished in the 1970s. We also know that that building underwent some additions, as a second floor was added sometime in the nineteenth century. Additionally, we know that in 1770, a German, John Yeakel purchased 104 acres that included the Log House that the Morgans purchased in 1708. He is the first German on record to buy the property. In 1774 he sold 82 acres with “fair improvements” to Yellis Cassel, another German, for almost double what he paid for it. “Fair improvements” could mean simply the clearing of land or the building of a new structure. John Yeakel probably did not live in the house since he already owned property in Franconia. He may have bought it and “flipped” it for a profit.

This somewhat abbreviated history of the restoration of the house shows the uncertainty of history. Often, records are not as good as we can hope. We can use what we have: a mixture of science and history: in order to try to come to a fuller understanding of the building and the people that lived there. We think that the story I just told you: of a small, meager one room building that was expanded towards the end of the century: is relatively accurate. We think that based on historical evidence, scientific research, and our best, informed guesses. However, the maddening thing about history is that that might not be the case. Research continues and research can lead to changes. While that it is maddening, it is also very exciting.

The more maddening thing, though, is that the original Morgan Log House no longer exists. It’s foundation does, but was replaced with a construction built in the 1970s. This makes it very difficult to deduce what the lived life experience at home would have been for Edward and Elizabeth.

We do know that they had a hearth, which would have dominated the outside wall and would have been used for the cooking of foods. We do know that they did not have a second floor, but they did have a basement, which might have been used for storage, serving as a sort of root cellar.

Since the structure is gone, though, it it really our best guess.

What sort of property did the Morgan’s own besides the dwelling house?

Their possessions, again, fall into the we don’t know column. So what’s a historian to do? We can go to the next best thing–their child Morgan Morgan, who signed his will in 1727 a probate inventory was conducted of Morgan’s property after his death. with his wife Dorothy serving as executrix.

The property listed is far from luxury goods–most is items used in everyday life. There is one bed and some furniture, two spinning wheels, two coverlets and a blanket, one churn, some barrels, a pot and kettle, kitchen implements, jugs, a Bible and some other books, a chest, table, and chairs, farming equipment (including axes, scythes, and harrows), as well as a musket, a powder horn, some carpenter tools, ropes, and a grindstone. Animals listed include a horse, a mare and a colt, a young gray horse, three mares, nine horned cattle, eleven sheep, a parcel of swine. Also listed are wheat, barley, the land itself and corn. An indentured servant named Joseph Griffith (valued at 5 pounds) is listed. The entire estate is valued at 271 pounds, 10 shillings. Not a large estate, but not a small one either.

This is, of course, not necessarily what Edward and Elizabeth owned, but chances are it isn’t far from the mark. The objects that Morgan Morgan owned at the time of his death are the house, things used for cooking, a meager collection of furniture, a Bible and some books: but mostly things connected to the farm. It is very safe to assume that Edward and Elizabeth lived under similar means.

So, from this, what can we glean about the lives of Edward and Elizabeth Morgan? Though we don’t know too much about them as people, we can infer quite a great deal.

First, they were immigrants. Like their fellow Welsh Quaker immigrants, they were willing to risk dying on an ocean voyage for the opportunities that Penn’s Woods would grant them–opportunities of religious expression and prosperity.

Likewise, they were Quakers. They are part of a community of faith. While it is very difficult to assume their engagement in their faith, we know that they took part in the community, celebrating marriages at the meeting house and taking part in important community milestones.

Thirdly, we know that they were farmers, tilling the land that surrounded their home. First three hundred acres than eight hundred acres. We know that they grew crops and materials to aid Edward’s cloth making business.

Edward and Elizabeth’s story is one thread in the fabric of our national story that we should all be constantly reminded of–we are a nation of immigrants. Many that came to this country with nothing, with uncertain prospects. Refugees escaping persecution and hoping for inclusion here. Their story is our story–the American story.