One of the things that we are always interested in is attempting to contextualize the Morgan Log House within the period in which it was built. In thinking about our new federal holiday, Juneteenth (which commemorates the emancipation of enslaved people), it is fitting that we think about how the atrocity of enslavement touched the colony (and eventual commonwealth) of Pennsylvania. While there are no historical sources that point to enslavement occurring on the farm that would later be known as the Morgan Log House, the history of the house occurred in the context of the transatlantic slave trade, in the world that enslavement built.

Though William Penn and the Quakers who helped form Pennsylvania were early proponents of abolition, slavery still became part of the Pennsylvania colony. The history of Pennsylvania shows a complicated relationship with the institution of slavery. A tax was introduced in 1700 on imported enslaved individuals in an effort to minimize slavery in the colony. A 1725 colony law demanded that, if an enslaved person was freed, their former enslaver must secure a bond in case that individual became reliant on the public welfare. The law further limited the economic options available to free people of color, and fined ministers for marrying free people of color. In 1780, Pennsylvania passed its Gradual Abolition Act, which repealed the more restrictive 1725 law. It was the first democratically adopted piece of legislation for the abolition of slavery in the world and decreed that persons born to an enslaved woman after 1780 would be indentured servants until they were 28, then they would be set free. Additionally, non-resident enslavers would have to free their enslaved people if they resided in the state for six months (this was exempted for Members of Congress). While staying in Philadelphia, George Washington had his enslaved individuals return to Mount Vernon every six months to avoid this law. In 1793, the new United States Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, which noted that it was the duty of the state to arrest and return runaway enslaved people and that individuals hiding or aiding runaways could be fined. Washington signed it into law. Slavery continued into the nineteenth century when it was abolished in 1865 through the 13th Amendment. Juneteenth is celebrated to commemorate the arrival of Union troops in Galveston, Texas, and the reading of General Order 3, which freed enslaved people: two and a half years after Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. It marked the end of legalized slavery in the United States. Reconstruction, as well as subsequent decades and continued struggles for equal rights and non-discrimination, show that the nation continues towards a more perfect union of rights for all.

Closer to the Morgan Log House, enslaved individuals were recorded in census data in Montgomery County from 1790 onwards. In 1790, 113 people were enslaved (there were 440 free people of color). By 1800, 33 (537 free people of color). Three (3) in both 1810 (671 free people of color) and 1820 (874 free people of color). The last recorded enslaved individual in the county was in 1830 (there were 743 free people of color). Enslavement was not a solely “Southern” phenomenon: it occurred throughout the nation.

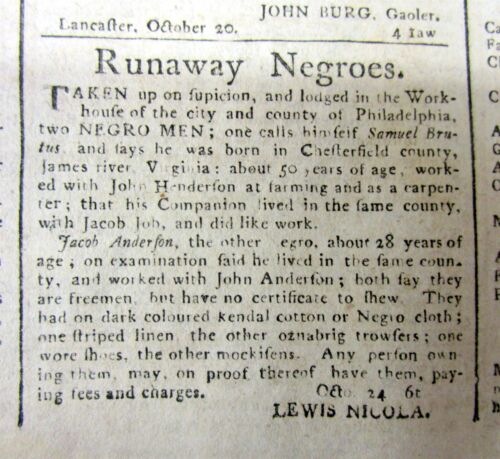

Enslavement was brutal and attempted to strip people of their humanity. We can find glimpses of the people who were enslaved in an unlikely source: runaway advertisements that were placed in newspapers. These advertisements were placed by enslavers demanding the return of people that they believed to be their property. These ads are a window (albeit a small and very biased window) into the lives of people who lived in Pennsylvania who were said to be the property of someone else.

For this Juneteenth, we would like to look at a selection of “runaway” advertisements from the Pennsylvania Packet and the Pennsylvania Gazette, published in Philadelphia. This is a small slice of a much larger collection of ads, placed throughout the eighteenth century.

Each of these ads represents a person: a person with hopes, dreams, feelings, and emotions: who someone paid for and believed to be their property, many living in a new nation with “self-evident truths” that did not, in law anyway, apply to them.

We have chosen to quote the ads as they originally appeared.

“SIXTY DOLLARS REWARD. RAN AWAY from the subscriber, in the township of Ridley, and county of Chester, a Mulatto man named JULAS, (has since changed his name to Alexander Bruce) about five feet ten inches high, has long straight hair somewhat like the Indians, walks a little stooping; he enlisted with Capt. Roach, and was sometime on board his galley: He left his masterservice the 26th of December, 1776. Any person taking up said run away and delivering him to his master, or to JEHU EYRE in Philadelphia, shall be entitled to the above Reward.ISAAC EYRE.” Pennsylvania Packet, December 8, 1778

“THIRTY DOLLARS REWARD. RUN AWAY from the subscriber, at Trenton Ferry, a Mulatto woman named RACHEL, a lusty tall woman, and very big with child; had on a striped lincey petticoat, and a large white cloth cloak; has with her a large bag of cloaths and a blanket: she pretends that she is free, as she has been stolen by a soldier these two years from her master, and has been in camp. She took with her a boy called BOB, about six years old, her own child, and appears to be white without close examination; the boy has on a brown cloth coat, oznabrigs overalls, shoes, and a hat with a gold ban round it; he appears sickly. Whoever takes up said woman and boy and secures them in any gaol, and gives information to Mr. Joseph Carlton, at the War Office, Philadelphia, or the subscriber at camp, shall have the above reward and reasonable charges, paid by MORDECAI GIST, Col. 3d Reg.” Pennsylvania Packet, October 15, 1778

“FIVE POUNDS REWARD. RAN AWAY from the subscriber, about four or five weeks ago, out of the city of Philadelphia, a Negro man named DICK, about four and a half feet high, 50 years old, has a lameness in his body; it is supposed he is gone to Bucks County, as he has a wife there. Whoever takes up the above Negro and brings him to the subscriber on market street wharf, Philadelphia, shall have the above reward and reasonable charges, paid by ROBERT TURNER.” The Pennsylvania Packet, July 25, 1778

“Eight Dollars Reward. WAS stolen from the subscriber, living in Moreland township, Philadelphia county, in the night of the 20th of this instant, by a Negro Man, who calls himself JOSEPH, the following articles, viz. one great coat of Bath coating, one tight bodied coat of broad cloth, one under vest of linsey, double breasted, one pair of corduroy breeches, two shirts, two pair of striped linen trowsers, two pair of new shoes, one pair of blue ribbed woolen stockings, one pair of silver buckles carved. Whoever takes up and secures said Negro (who is remarkably handsome for a Negro , being straight nosed, thin lipped, and very black, about five feet nine inches high) and secures him in any gaol, giving information thereof, shall be entitled to the above reward, and reasonable charges. RYNEAR LUKENS.” The Pennsylvania Gazette, April 24, 1793

“Run away from Mrs. Maybury, of Cushahopen, in Marlborough township, Philadelphia county, on Friday, m the 5th instant, a Spanish Negro man, named Booner, alias Mooner, is about 5 feet 6 inches high, of a yellowish hue, has a down look, and has a very foolish laugh: Had on when he went away, a light coloured kersey jacket, a pair of tow linnen trowsers, very good shoes, an ozenbrigs shirt, new cotton cap, and new felt hat. Whoever takes up and secures said Negro , so as his mistress may have him again, shall have Twenty shillings reward, and reasonable charges, paid by Mrs. Maybury.” The Pennsylvania Gazette, May 11, 1749

“RUN away on the 12th of April last, from Matthias Gmelin, glazier, in the township of Worcester, at Matachen, Philadelphia county, a Negro man, named Jack Tross, aged about 38 years, of middle stature, a big head, speaks good English, and some Dutch, and is left handed: Had on when he went away, a striped callimancoe jacket, new check trowsers, blue stockings, two shirts, one fine and the other coarse, good hat, and shoes with white metal buckles in them. Whoever takes up the said Negro Man, and secures him, so that his master may have him again, shall have Forty shillings, if taken in Pennsylvania, and if taken in any other province, Three Pounds reward, and reasonable charges, paid by MATTHIAS GMELIN.” The Pennsylvania Gazette, May 14, 1747

“RUN away the 17th of August, from Thomas Mayburry, at Hereford Furnace, in the County of Philadelphia, a Spanish Negro Man, named Mona, of about 28 or 30 Years of Age, of middle Stature, thin Visage, very full of Flattery, apt to laugh, and talks broken English: Had on when he went away, an Oznabrigs Shirt, check’d Linnen Trowsers, old Hat, old double Worsted Cap, no Shoes nor Stockings; had some Money, suppos’d to be given him by the Papist Priest. Whoever takes up and secures said Negro Man, so that his Master may have him again, shall have Forty Shillings Reward, and reasonable Charges, paid by Thomas Mayburry. N.B. All Masters of Vessels are desired not to harbour him on board, or carry him off.” The Pennsylvania Gazette, September 4, 1746

We encourage you to explore more about this time in our nation’s history at the following resources:

- Freedom on the Move: A Database of fugitives from American slavery

- Juneteenth, National Museum of African American History and Culture

- Slave Voyages: Explore the Origins and Forced Relocations of Enslaved Africans Across the Atlantic World

- Voices from the Days of Slavery: Stories, Songs,and Memories at the Library of Congress

- Slavery and Underground Railroad Resources, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission

- African American Resources for Pennsylvania, Family Search