“We shall continue the utmost Vigilance against this most dangerous Enemy,” wrote George Washington in a letter to John Hancock on the 21st of July, 1775, after receiving command of the Continental Army. Washington certainly had many dangerous enemies to consider: British Regulars, Loyalists, Hessian Soldiers, and indigenous allies of Britain. His letter to Hancock expresses concern about an unseen enemy: the smallpox virus. As he mentioned in the same letter, “I have been particularly attentive to the least Symptoms of the small Pox and hitherto we have been so fortunate, as to have every Person removed so soon, as not only to prevent any Communication, but any Alarm or Apprehension it might give in the Camp.”

This is a blog post about smallpox inoculation and the American Revolution, as well as the changing ideas that brought the idea of inoculation from something to be feared and avoided to something that was part of Washington’s public policy. Further, it makes the case that fighting of disease, especially through variolation and inoculation and later through vaccination, is a very American pursuit.

The Pox and America

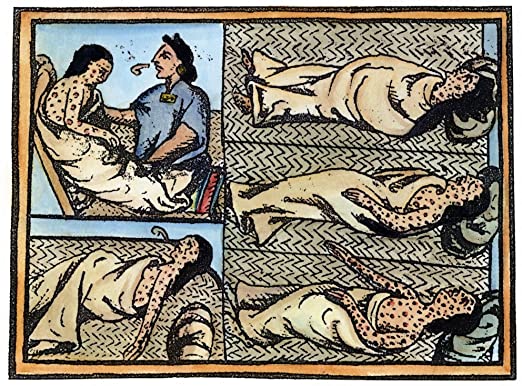

Smallpox was a great threat throughout the colonies, and had wracked through the Americas since European contact with the New World in the fifteenth century. Indigenous Americans, who had no resistance to the disease, encountered Europeans who had built up immunity but were still disease carries. Smallpox plowed through the indigenous world like a tsunami, destroying complex societies and making it possible for Europeans to gain control of the Americas. This also led tot he loss of intangible culture like stories, knowledge, and lifeways. While some culture remained, the trauma of colonization and the disease that followed it should not be ignored. As the Spanish friar Toribio de Benavente Motolinia noted in his early 16th account of Mexico, “As the Indians did not know the remedy of the disease…they died in heaps, like bedbugs. In many places it happened that everyone in a house died and, as it was impossible to bury the great number of dead, they pulled down the houses over them so that their homes become their tombs.” These outbreaks continued, rolling through the Americas into the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries in epidemic waves.

Smallpox is a horrific, debilitating disease. Onset of the disease was sudden and brutal. It pitted the skin, could cause eyebrows and eyelashes to fall out, could cause severe blindness, neurological disease, and blindness. In some instances, it caused infertility. Some lived, but many died. Those that lived often experienced ostracism and withdrew from society. Suicide rates among those who had survived smallpox and were disfigured, was disproportionally high. It could be transferred easily and quickly, which meant that the spread of smallpox was quick, violent, and deadly.

Smallpox was not just an American problem, but a global one. In the modern world, we consider the idea of globalization something new. However, a global world existed early on. It could be argued that the Mediterranean World in the ancient world was global, and that Medieval Europe was in strong contact with Asia and Africa. Most certainly, at the time of European contact with the New World, the world was connected by a vast global system that connected the Americas, Africa, Europe, and Asia in a complex web of trade, movement, and interaction.

While it might be easy to consider people living in colonial America as being quite disconnected from the world, in reality they lived in a very global society-especially people living in port cities. The port of Philadelphia was the largest port in the British colonies in the Americas, and would have received ships from all over the Explosions of smallpox were common. As were epidemics of yellow fever, scarlet fever, and malaria, as well as waves of venereal disease.

The American Revolution

The American Revolution was a global event that involved American colonists as well as British, French, and Hessian soldiers, as well as indigenous actors who were aligned to one side or the other. In short, while it was an American Revolution, it was occurring on a very global context with a wide variety of people being pulled together.

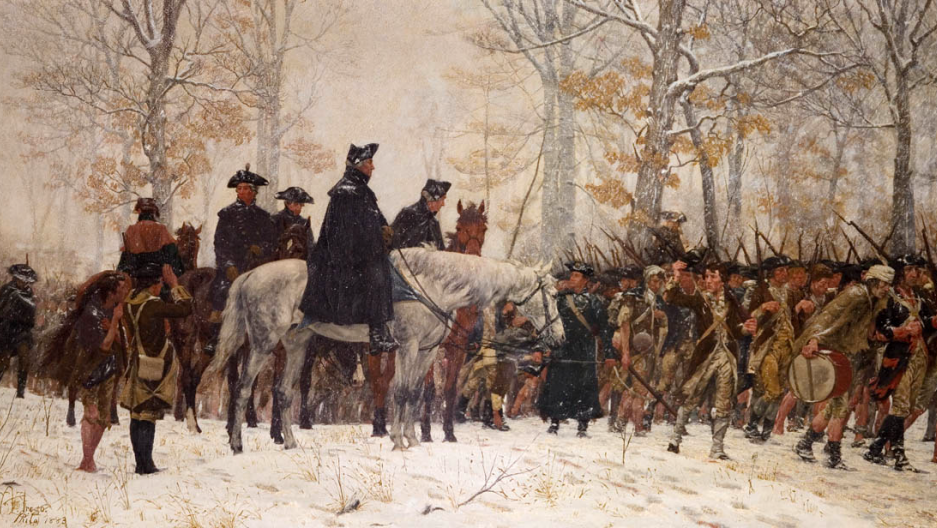

As a result of this, smallpox and the American Revolution were intrinsically connected. When Washington wrote to Hancock in 1775 he was acknowledging a known reality: that the epidemic of smallpox was decimating American troops and, possibly, could be making the American Revolution unwinnable. It proved to be crippling for two major campaigns through 1775 and 1776, especially in the siege of Boston and the Battle of the Cedars in Quebec. In Quebec, 10,000 Continental Troops contracted the disease, requiring the army to retreat from Quebec. General Horatio Gates wrote to Washington, noting that “Every thing about this army is infected with the pestilence; the cloathes [sic], the air, the ground they walk upon. To put this evil from us, a general hospital is established at Fort George, where there are now between two and three thousand sick.” Often dramatic in letters and in life, John Adams reacted to the army’s collapse by writing “The Smallpox! The smallpox! What shall we do with it!” The army crippled, Washington regrouped.

At that time the army had two deadly foes: the British Army and the Smallpox virus.

Variolation for smallpox had existed in the Americas for a long time, especially among Native Americans and African populations, who often taught variolation to colonists. As a result of this, variolation was often considered a heathen and uncivilized process. Likewise, clergymen railed against it, noting that it was combating the will of God, who was seen as having caused the disease as a divine punishment.

Cotton Mather and Zabiediel Boylston had inoculated people in the Boston Smallpox epidemic of 1721. Variolation involved purposely infecting someone with the smallpox disease, which would cause a small infection of the disease (that was easier to overcome than the actual disease). The variolated would receive lifelong immunity to the disease. After inoculation, the patient would become contagious with the disease, which required quarantining. It worked, but had its risks. Being given a live dose of the virus, it was possible that the inoculated could die. Likewise, it was possible that they could spread the disease and cause a further outbreak.

Inoculation for smallpox was illegal, and Washington threatened punishment for the use of inoculation. As he wrote in his General Orders of May 20, 1776, “No Person whatever, belonging to the Army, is to be inoculated for the Small-Pox—those who have already undergone that operation, or who may be seized with Symptoms of that disorder, are immediately to be removed. . . . . Any disobedience to this order, will be most severely punished.” This reluctance might have been, at first, to the detriment of the army under his command. It is important to remember, though, that variolation was not risk free. It could cause further crippling to the army, killing more from the disease. It could cause further spread of the disease. Likewise, it would cause the temporary stopping of the army, because of the necessary quarantine period to avoid the spread of the disease after inoculation. Simply, avoiding inoculation and quarantining seemed to be the safest option in the early years of the war.

That position quickly became untenable. Washington experienced a change of heart, in part to the threat of the disease to his army and because of growing scientific evidence that variolation was an effective way to overcome the disease. It should be noted that Washington had a long experience with smallpox, having contracted the disease in Barbados in 1751 and nearly dying. It had left him pox marked and, probably, unable to father children. It became apparent that quarantining was not working, and that it would be better to inoculate the troops, and ordered mandatory smallpox inoculation of his troops in 1777. By the end of the year, 40,000 of the troops were inoculated. Most importantly, the infection rate dramatically dipped from 17% to 1%, which was an exceptional success. Washington’s defeat of the smallpox virus through variolation was an important moment in the history of the American Revolution that is often ignored, it also marks the first time that an entire army had been successfully inoculated for a disease. Shortly after, the Continental Congress legalized variolation throughout America, endorsing Washington’s plan through legislation.

Vaccination: A Coda

Inoculation worked, but came with many risks. Disease could be transmitted. Risks would be further minimized by Edward Jenner, an English physician and scientist who pioneered the idea of the vaccine through the smallpox vaccine, the first functional vaccine. Jenner showed that through infection with the mild cowpox, patients experienced immunity from the much more deadly smallpox virus. Jenner inoculated James Phipps, an eight year old boy who was the son of his gardener. The boy received a small reaction, but no infection. The early precursors of modern vaccination was born, and it could be argued that Jenner saved more people from death than anyone who had come before.

Vaccination came to America by way of Benjamin Waterhouse, a friend of Jenner who brought it to the new nation, and led to the further crippling of the dreaded virus.

In 1980, the World Health Organization declared that smallpox was eradicated, Jenner’s legacy.

While variolation was soon superseded by the safer and more sure method of vaccination, modern Americans owe a great debt to Washington’s eventual use of inoculation to lessen the impact of smallpox throughout the American Revolution. The war was complex and involved many people from many parts of the world and walks of life, with a variety of different political ideologies and views of the world. It should also be noted that the result of the American Revolution, the free new republic of the United States of America, was not a foregone conclusion. Americans broke free from the British empire and unleashed the wrath of the largest fighting force on the planet. A successful revolution was not the likely conclusion, but, rather, the hanging of the founding fathers as traitors. Many factors ended up just right for the revolution to end the way it did, including American military victories, the success of American imperial alliances (leveraging the French and Spanish against their longtime adversary England), as well as the war weariness of the British Parliament. It could be argued, though, that without caring for the smallpox problem, the revolution could have ended in a very different way.

The Americans needed to defeat the invisible enemy of the smallpox virus before they could defeat the enemy with the red coats.

Selected Bibliography

Ann M. Backer, “Smallpox in Washington’s Army: Strategic Implications of the Disease During the American Revolutionary War,” Journal of Military History 68 (2004): 381-430.

Benjamin A. Drew, “George Washington and Smallpox: A Revolutionary Hero and Public Health Activist,” Journal of the American Medical Association Dermatology 151 (2015): 706.

Sarah Schuetze, “Carrying Home the Enemy: Smallpox and Revolution in American Love and Letters, 1775-1776.” Early American Literature (2018): 97-125.

N.J. Willis, “Edward Jenner and the Eradication of Smallpox,” Scottish Medical Journal 42 (4): 118-21.