Often, we think of history as being done by looking at documents and material artifacts and using them to make inferences about what happened in the past. Historians do that a lot, and it remains to be the most effective tool for learning about the past.

With the rise of computers and technology, historians can use all sorts of new tools to look at historical data. This blog post looks at using one of them: the word cloud, to try to understand the diaries of William Leister in a more holistic way, and try to find trends across the text.

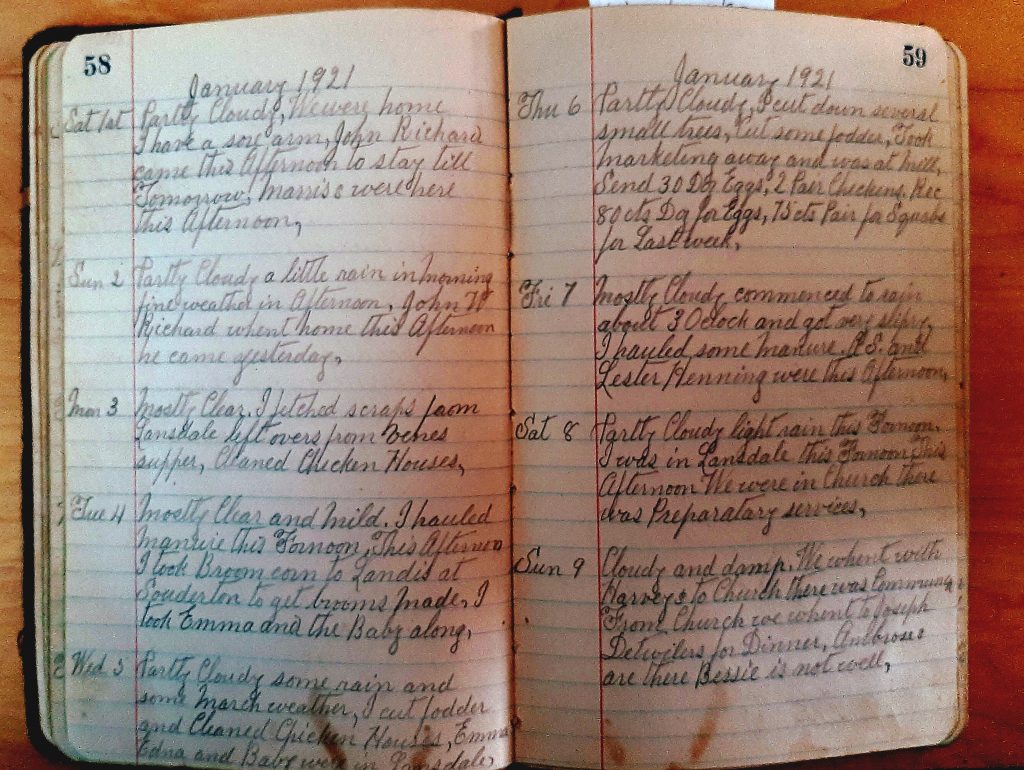

Some background first: the diaries are a collection of daily accounts of the life of William Leister, a Towmanecin Farmer who lived at the corner of Weikel and Allentown Roads, a stone’s throw from the Morgan Log House. They were gifted to us in 2018 by Brian Hagey. They form the basis of our current temporary exhibit, “A Day in the Life of a Farmer.” For more about William Leister, click here.

The diaries of William Leister are really five texts: one from 1911 to 1913 (2018.001.001), one from 1913 to 1916 (2018.001.002), one from 1920 to 1923 (2018.001.003), one from 1924 to 1927 (2018.001.004) and one from 1927 to 1934 (2018.001.005). Side note: These identifications, such as 2018.001.001 are accession numbers: museums use them to track objects in their care, and from them we know a lot about each object just by looking at its number. We know that 2018.001.001 was donated in 2018, that it was the first accession of that year (2018.001 refers to the donation that contained the diaries) and it was the first item in that donation. Another donation that occurred in 2018 would be 2018.002, which would have been donated by another person and would be unrelated.

Here’s what we did for this project. We had previously transcribed the entirety of the five diaries, keeping William Leister’s linguistic peculiarities to maintain his voice, which stays true to the original documents. We uploaded the text of each diary into an algorithm that generated a word cloud. To do this, we used a word cloud generator, which takes a large body of text, runs it through an algorithm, and creates a word cloud out of it. You can find by clicking here. You can even make your own word cloud with any text that you might have!

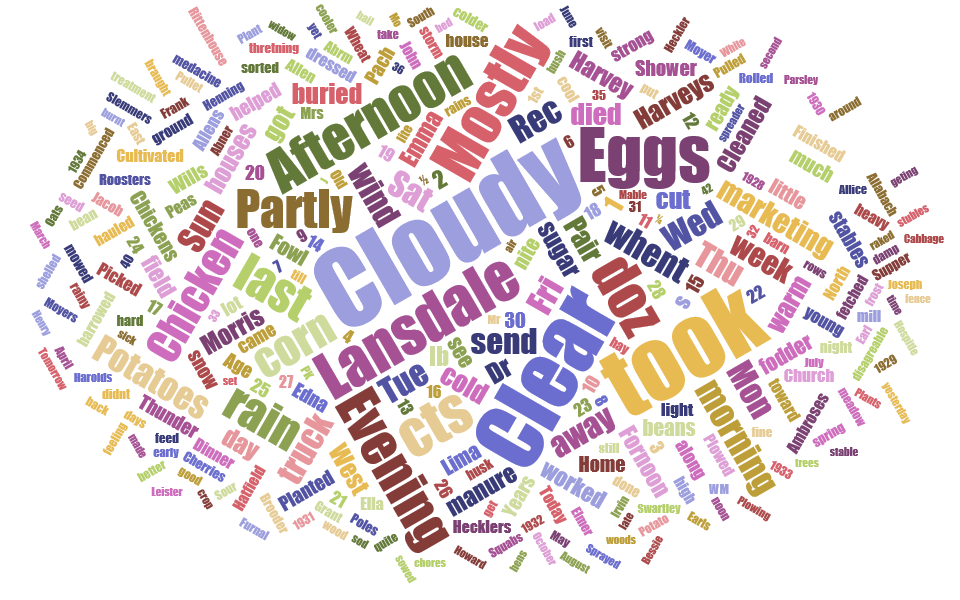

How does a word cloud work? Word clouds record and visualize the recurrence of certain words in a text. The more times a word appears, the larger that word will appear in the cloud. The less times that word appears, the smaller it will be. This generator allows for us to choose how many words are depicted in the cloud. The examples we’re using here are generated using the top 300 words from the text. Of course, there are words that William Leister used infrequently that do not appear in the word clouds (they occur with less instances than the top 300 words).

Below you can see each of the word clouds we generated.

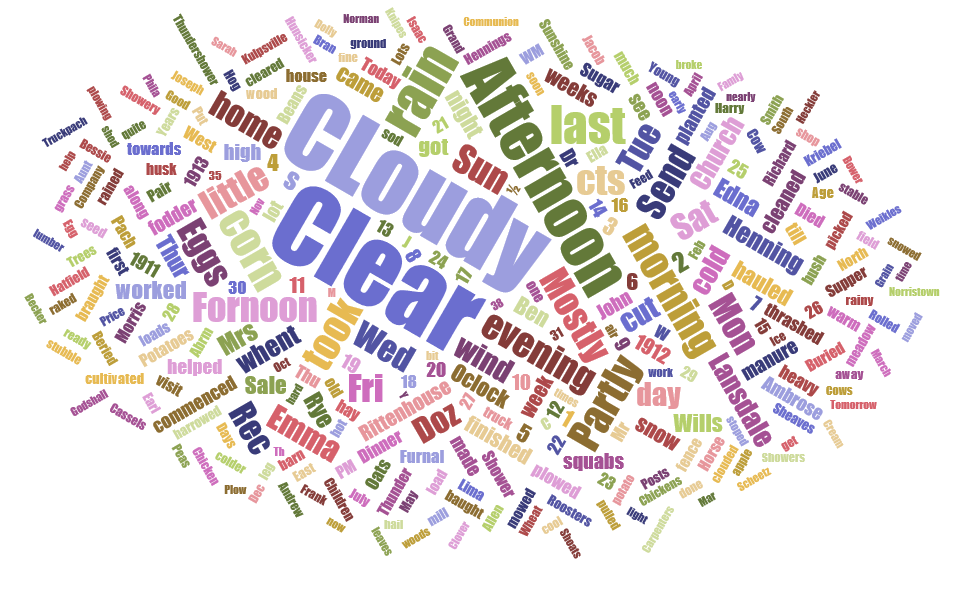

2018.001.001, 1911-1913

2018.001.002, 1913-1916

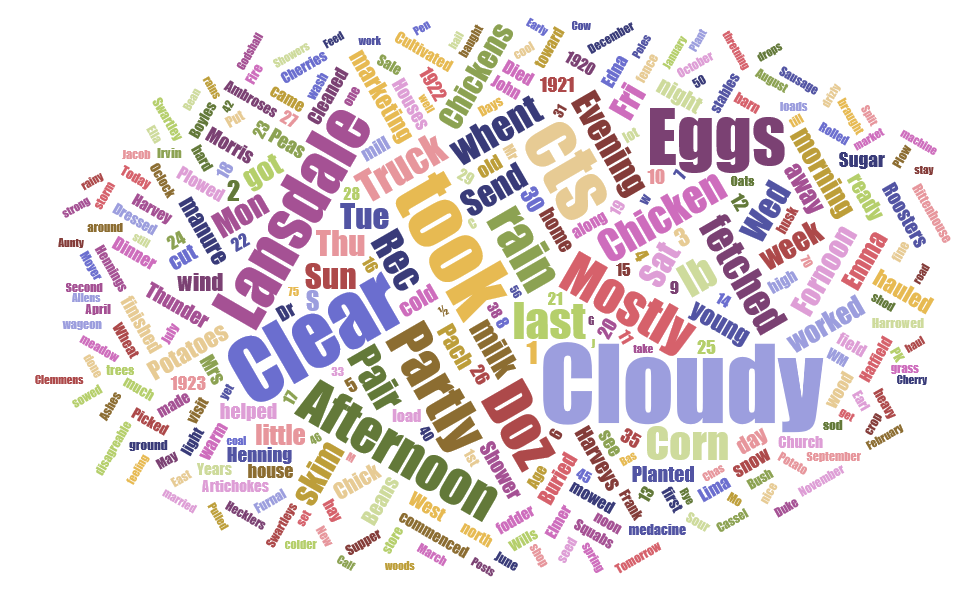

2018.001.003, 1920-1923

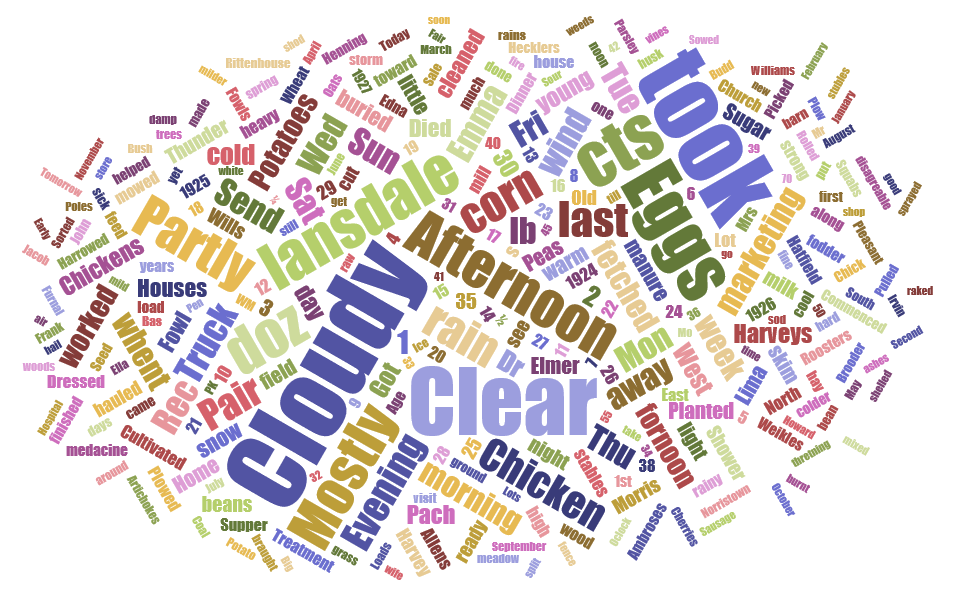

2018.001.004, 1924-1927

2018.001.005, 1927-1934

Here’s some information we can pull from this. There is a lot more, but for the sake of brevity, let’s focus on a couple things:

Weather

William Leister’s diaries are a text about the weather: he records the weather every day. It’s no surprise, then, that weather words dominate the Word Clouds from his diary. For example, all five show the large presence of “Cloudy” and “Clear,” two very simple weather words that could apply to a lot of days depending on season. Likewise, appearing smaller, are more descriptive words, such as “sunshine,” “thundershower,” “warm,” “rained,” which are more specific. Of course, Leister uses different words to describe the same sorts weather often, which would mean that the word would appear smaller (such as rained, shower, wet, and poured).

As a farmer, weather would have been incredibly important to William Leister and would have played an important role in the way he structured his life. This would hold true for his fellow farmers in early twentieth century Towamencin, as well as settlers and farmers in earlier centuries, such as the Morgans and Cassels who lived in the Morgan Log House. Then, as now, the weather was an important part of crops and livelihood for an agrarian community.

Crops

From the word clouds, we can also see many mentions of crops that William Leister was growing and selling.

In this, there is one interesting trend that jumps out, which is the sharp increase of size in the words “eggs” and “chicken” from the first diary in 1911-1913 through the last diary in 1927-1934. Throughout the diaries, William Leister makes an accounting of the chickens and eggs that he sells at market. It appears, though, that chickens and eggs gain much more prominence in the later diaries.

Why could that be? It could be a quirk of the text: maybe he just recounted chickens and eggs more. However, there could be something to it. As the diaries go on, William Leister ages and begins to complain more about physical ailments. It could be that, as he aged, tending chickens and selling both chickens and eggs became an easier task for an aging body (though he never gives up on the growing of other crops). It could also be that chicken and egg prices increased through the Great Depression.

Other crops appear smaller throughout the word clouds, and are the sorts of crops that he mentions frequently. These include things such as potatoes and corn, which appear as a constant size throughout, which is in keeping with the text of the diaries themselves. Included also are other crops that he mentions with less regularity, such as artichokes, cherries, oats, beans, and apples.

People

Prominent throughout the word clouds (and the diaries themselves) are people from William Leister’s social orbit. These include Emma, his second wife, who was the sister of his first wife, May, who died in 1904. Emma was married into the Henning family, and the Hennings frequently appear throughout the text (as they do in the word clouds). Likewise, Leister talks about his children: Edna (who married Harvey Hecker, both of which appear in the diaries. William Leister often refers to both Edna and Harvey as “Harveys”). According to the 1920 census, William is living with his wife Emma, his daughter Edna, her husband Harvey, and their daughter (his granddaughter).

Also mentioned in the diaries (and the word clouds) are people who Leister interacts with: people like Rittenhouse, who operated the farm across the street and Kriebel, who Leister often borrowed farm machinery from.

Another person adjacent item that can be pulled from the diaries is “died.” Throughout his diaries, William Leister recounts local deaths, and makes notations for when people died. He also notes when each person was buried. Other important occurrences that he makes notations for include “married,” and “born.”

Place Names

Another thing that appears in the diaries and their word clouds are place names. Prominent throughout is Lansdale, which makes a lot of sense given that William Leister did a weekly run to the Lansdale farmer’s market to sell his goods.

Likewise, place names such as Kulpsville, Hatfield, and Norristown show the evidence of various errands.

Leister also frequently accounts for going to church, which appears throughout the word clouds as well.

Some parting thoughts:

With just this quick look at reading the diaries through a tool like the word cloud, we can learn a lot about the texts as a whole. Of course, we miss the things that he accounts for only once, we miss the peculiarities of speech, and we miss context. But, in conjunction with a deep reading of a text like this, visualization tools like word clouds can tell historians a lot about documents that they are working with.

You can see the diaries, as well as the word clouds, in our temporary exhibit A Day in the Life of a Farmer, on a regular tour of the Morgan Log House. To pre-schedule a tour, and to learn about our COVID-19 safety protocols, you can click here.