Often, when visiting a museum, we don’t think about how the objects that we see were brought into being. They exist as objects to be looked at but not understood in a practical way.

This exhibit looks at a selection of objects that are similar to ones that might have been used in the Morgan Log House in the eighteenth century.

In the fold out sections below, explore a selection of objects from the Morgan Log House’s collection and how they would have been made and used in the eighteenth century.

It was on display in the temporary exhibit gallery of the Morgan Log House for the 2017 season.

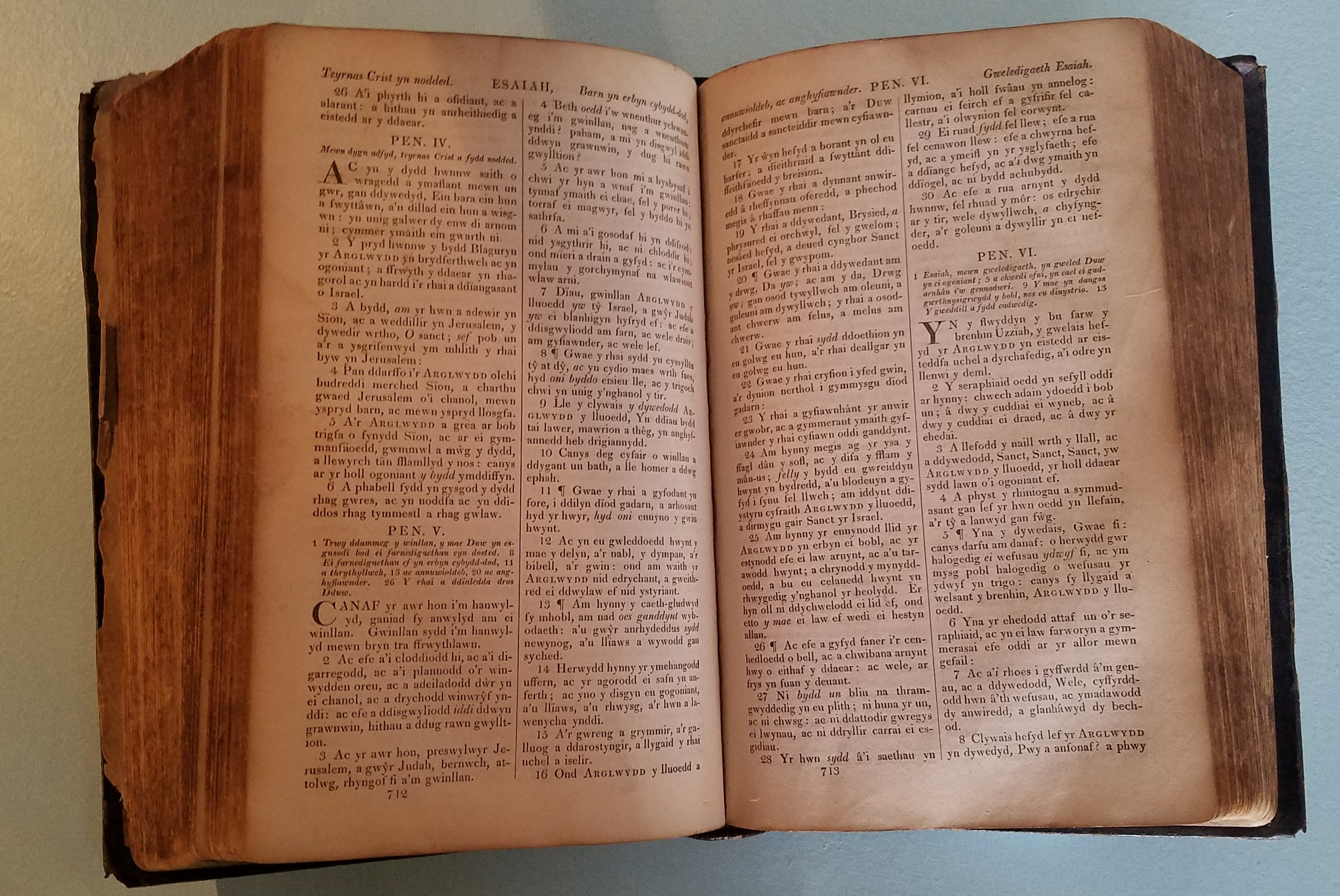

Welsh Bible, c. 1837

Letters were carved, by hand, out of metal punches and set into trays. Type had to be set backwards to produce the correct print. Trays were inked and placed into the press. Paper was placed over the trays. When pushed through the press, ink transferred onto the page, creating a printed sheet. Each sheet was printed multiple times before moving to the next set page. This was slow and taxing work. It could take a long time to set type for a page, one newspaper sheet could take eight hours! An efficient team of printers could produce between 180 and 240 pages an hour, over a fourteen-hour workday.

To construct a book, pages were first organized into signatures of eight to twelve pages. Many signatures were then sewn together to create the inside of the book, which was sewn into a cover. Covers were usually made of stretched leather over boards. Often, as is the case with this Bible, the leather was punched and stamped with decoration.

This particular Bible was produced by the British Foreign Bible Society and was meant to be used to preserve the Welsh Language throughout the world.

Iron Pot, Mid 18th Century

The iron industry blossomed in eighteenth century Pennsylvania as a result of abundant ore and coal. Cast iron cooking implements had been manufactured since antiquity. To make cast iron, pig iron was melted down to remove impurities. It was them poured into molds, which were often made out of sand, yielding a finished product.

This sort of pot would have been used for preparing meals over an open hearth. While it might be tempting to think of open hearth cooking as simply holding pots over an open fire, it was a complex system of knowing about changing temperatures and conditions. Pots such as this would have been placed in warm coals somewhere inside the hearth to cook or could have been hung above the fire on a crane, which could be positioned closer or farther from the flame as needed.

Did You Know?

The lid of this pot is newer than the pot itself and was probably forged in the nineteenth century. This could show that the pot was used into the 1800’s.

Eyeglasses, c. 1760

An early handheld precursor to today’s eyeglasses was first invented in the thirteenth century. Such spectacles were often used by those who did not wish to be seen wearing glasses (George Washington included). As printed books became more popular and available, demand for eyeglasses increased, which lead to increased production and availability.

For much of the colonial period, eyeglasses were imported from England. John McAllister Sr. opened the first optical shop in Philadelphia in 1799. After the War of 1812, glasses started to be made in the new United States.

These glasses were probably imported from Great Britain and purchased locally towards the end of the eighteenth century.

Two Chairs, Eighteenth Century

The chair on the right is a Chippendale side chair that was produced at the end of the eighteenth century. The style is named after Thomas Chippendale, a British carpenter who wrote The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director, a guidebook for craftsmen creating English furniture. The guidebook was used in England and the colonies, and as a result a Chippendale piece might not have been created in the workshop of Thomas Chippendale. It represents one of the first cases of international mass production. However, Chippendale chairs were highly prized furniture pieces.

The chair on the left is an example of an eighteenth century ladderback chair with a rushed seat. Such a chair would have been made by a local craftsman. While it would require skill and specialized tools to make it, it would have been more financially available for the people who lived in this house.

Did You Know?

Chippendale furniture was the first example of a British furniture style that was named for the designer rather than the reigning monarch. Earlier examples include Carolinian and Georgian.

Interested in looking at the Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director? You can access it at Archive.org courtesy of the Smithsonian here.

Hay Fork, c. 1800

Additionally, tools were not mass produced in factories. Rather, they were produced by skilled hands for a necessary purpose. Tools were primarily made with utility in mind. Metal tools would be forged by a local blacksmith at the request of the laborer who needed them. Additionally, tools could be made from whatever was on hand. While this hayfork was produced by someone that clearly knew their way around a carpenter’s bench, other hayforks were made out of whatever pieces of wood were handy–even whole tree branches.